How History Books Get It Wrong

- DesignShed Org

- Jul 24, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 11, 2023

Scholar Anita Bakshi is taking on what's problematic about the way NJ’s Indigenous history is presented, by changing how it's accessed.

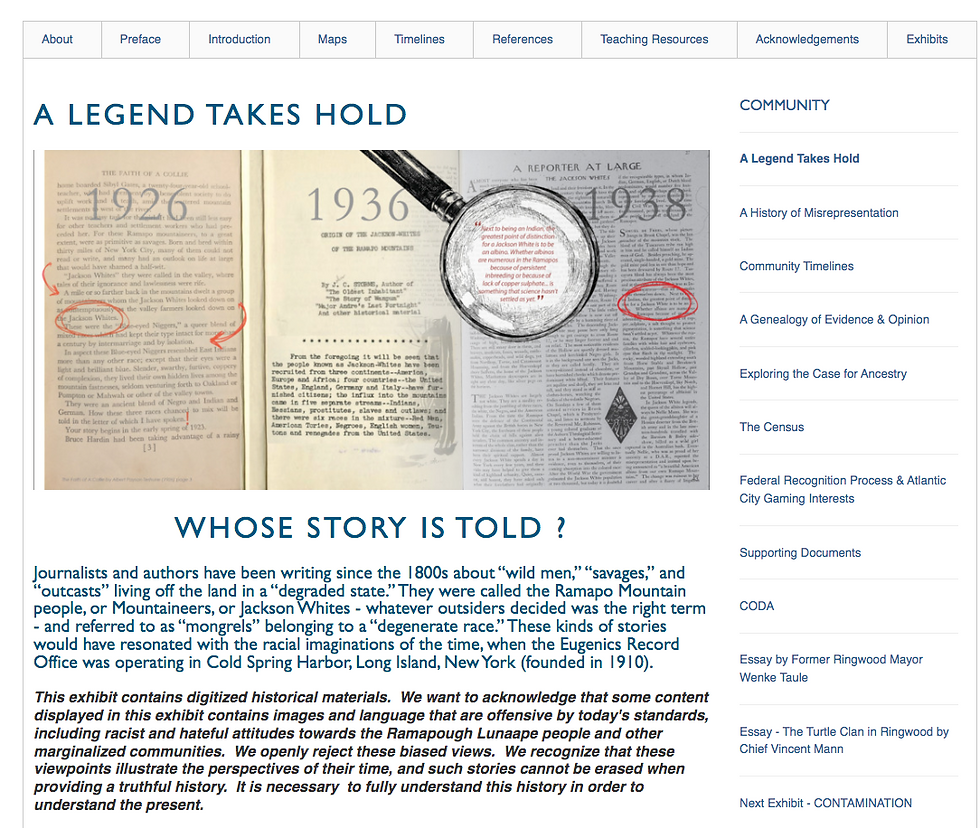

History of Misrepresentation Timeline. This timeline includes different representations of the Ramapough Lenape in the media. Credit: Our Land, Our Stories (2022)

For Issue 1, scholar and Dense advisor Anita Bakshi writes about how Ford’s 1950s car design and manufacturing, which adapted to the modern interstate’s faster speeds, has directly impacted the Ramapough Lunaape communities in Ringwood, New Jersey and surrounding areas. Her essay draws from a book she created through a collaborative process with the Turtle Clan, Our Land, Our Stories, and documentary Meaning of the Seed, which pulls from in-depth work with the Ramapough Lunaape Turtle Clan and scholars in archaeology, environmental medicine, history, and more to make known the detrimental effects of Ford’s contamination.

Here cofounder and editor Lune Ames talks with Bakshi about the challenges of this ongoing research since Issue 1, as well as its culmination into a digital exhibition for Rutgers University Libraries to be accessible as a community archive and multimedia curriculum for public education.

Anita Bakshi (center) with Ramapough Lunaape Turtle Clan Chief Vincent Mann (left) and project partner Dr. Chuck Stead (right) at the opening of the Our Land, Our Stories exhibit at the Newark Public Library in 2019.

LUNE AMES: How has your work with the Ramapough Lunaape continued since last fall? You’ve been working on a second edition of Our Land, Our Stories, so how has that been progressing and how have you hoped to expand the narrative?

ANITA BAKSHI: For the second edition of the book, I’ve decided to tackle head-on some really problematic scholarship that presents a very limited view of Indigenous history in New Jersey.

A university press wanted to publish the book, but then they backed off because a reviewer, who they said was a very well-qualified historian, claimed that our research isn’t the right history and instead pointed to a book written in 1974 research they said “proved” that the Ramapough Lunaape are not really Native American — just repeating discredited scholarship from decades ago. Then the whole project fell through and they didn’t publish it.

I wanted to have a place where there is a clear refute of that work and response to it, so there is a lot of new stuff in the second edition that goes into that history. I worked closely with Chief Mann and Clan Mother Michaeline Picaro who sent me a lot of materials, including horrible depictions of how the Ramapough have been represented in the past and still today by Facebook groups whose authors actively spread hate. As I engaged with such damaging scholarship, I felt contaminated by it with my own role as an academic given what the Ramapough have gone through because of it. But it really felt necessary to excavate all of that material.

"The Meaning of the Seed," Documentary Film.

LA: Using the work as a site for resistance is so powerful. What has been helpful as you continue to work on the second edition?

AB: As much as this dominant narrative is still blocking avenues, there’s so much support for shifting that ground and changing things. We’re all geared up to print this ourselves with grant support from the New Jersey Council for the Humanities and Rutgers University.

I’ve also been working on an Our Land, Our Stories digital exhibition with Rutgers University library. The material draws from the book, the Meaning of the Seed film, and short video projects that we’ve done. It’s a lot more interactive with really cool maps and embedded GIFs, so it’s even easier for teachers to use in the classroom. We really want to connect middle, high school, and university classrooms. Having this digital exhibit will make the information more accessible and easier for it to be utilized more thoroughly as a curriculum in teaching people.

Screenshot of Our Land, Our Stories, an online collaborative project with Rutgers University, Department of Landscape Architecture and the Ramapough Lunaape Nation.

LA: How do you see this archive continuing to evolve?

AB: It’s great that it can be updated without having to go to the printer. It gives us flexibility. As our community partners are growing and changing, we can facilitate their needs. For example, continuing to add more information about Munsee Three Sisters Medicinal Farm and the Ramapough because Clan Mother Michaeline Picaro is an incredible historian and has gathered so much. My hope for this is that we can use this as a place to organize and share their archives as a limitless classroom.

This can really become an archival resource where everything is linked and people can do their own research. I see this as the start for engaging more seriously with issues like environmental justice, Native American history, the census history, and ceremonial stone landscapes, all across New Jersey. There’s so much work that needs to be done here, and we can post and add new exhibits as we go. We can bring all of this to life and to the community. I don’t know quite how to say it but it’s something like we can democratize who does the scholarship.

Artists Jessica MacPhee and Lydia Zoe sketched while Turtle Clan members shared their stories at the exhibit opening. The sketches they created were incorporated, along with Ramapough stories, in the 2nd Edition of Our Land, Our Stories (forthcoming).

LA: That type of accessibility is so important. What’s considered valid research or scholarship so often excludes the public. What’s so valuable about your practice is that it engages “traditional” research methods while remaining critical of them, challenging who has knowledge and how we identify what’s considered valid. It’s participating in a scholarly body of work while also prioritizing communal histories and knowledge and communicating that to a public. How would you describe your research approach and what have you learned along the way?

AB: When I write books or articles, the text is its own thing – you write the text, you add your citations, you send the text for review, scholars revise and resubmit, reviewers read it. You’re always making changes to the text. Here we wanted to foreground Ramapough stories rather than just the academic voice. That was a big learning experience for me. We put the whole thing together in-house with my team, and the process looks very different. I write, then I go into InDesign, where I’ll shift around paragraphs in relation to the images that are there. The juxtaposition of information on the same page is really important.

A lot of academics don’t consider this a “real” book or academic work because it hasn’t gone through the standard peer review process.

But it has gone through its own type of peer review by our Ramapough community partners as well as scholars in environmental medicine, archaeology, history, and environmental studies. It brings in visual methodologies, narrative, and story in a serious way that still holds together as a serious academic text with citations and archival research. It’s a hybrid.

Anita Bakshi worked in architectural practice before doing a PhD with the Conflict in Cities research program. She moved back to the USA to teach at Rutgers in the Department of Landscape Architecture, and remains endlessly fascinated by the richness, diversity, contestation, and conflict embedded in New Jersey’s landscape.

Booth, Please is our weekly newsletter that explores the dreams, discoveries, confrontations, and epiphanies that emerge when design meets New Jersey — all set within the comforts of the world's diner capital. Subscribe below and cozy up every Sunday.

Comments